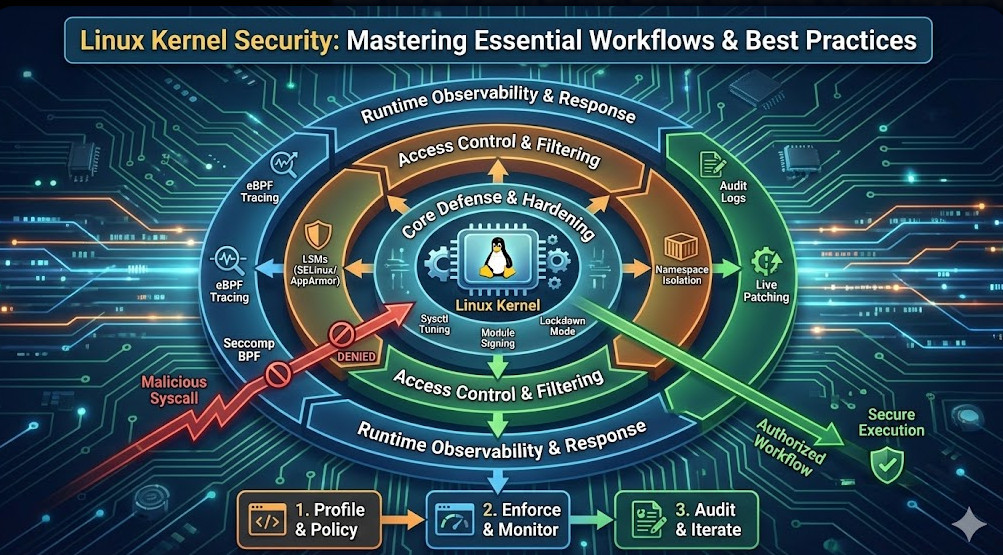

In the realm of high-performance infrastructure, the kernel is not just the engine; it is the ultimate arbiter of access. For expert Systems Engineers and SREs, Linux Kernel Security moves beyond simple package updates and firewall rules. It requires a comprehensive strategy involving surface reduction, advanced access controls, and runtime observability.

As containerization and microservices expose the kernel to new attack vectors—specifically container escapes and privilege escalation—relying solely on perimeter defense is insufficient. This guide dissects the architectural layers of kernel hardening, providing production-ready workflows for LSMs, Seccomp, and eBPF-based security to help you establish a robust defense-in-depth posture.

Table of Contents

1. The Defense-in-Depth Model: Beyond Discretionary Access

Standard Linux permissions (Discretionary Access Control, or DAC) are the first line of defense but are notoriously prone to user error and privilege escalation. To secure a production kernel, we must enforce Mandatory Access Control (MAC).

Leveraging Linux Security Modules (LSMs)

Whether you utilize SELinux (Red Hat ecosystem) or AppArmor (Debian/Ubuntu ecosystem), the goal is identical: confine processes to the minimum necessary privileges.

Pro-Tip: SELinux in CI/CD

Experts often disable SELinux (`setenforce 0`) when facing friction. Instead, useaudit2allowduring your staging pipeline to generate permissive modules automatically, ensuring production remains in `Enforcing` mode without breaking applications.

To analyze a denial and generate a custom policy module:

# 1. Search for denials in the audit log

grep "denied" /var/log/audit/audit.log

# 2. Pipe the denial into audit2allow to see why it failed

grep "httpd" /var/log/audit/audit.log | audit2allow -w

# 3. Generate a loadable kernel module (.pp)

grep "httpd" /var/log/audit/audit.log | audit2allow -M my_httpd_policy

# 4. Load the module

semodule -i my_httpd_policy.pp2. Reducing the Attack Surface via Sysctl Hardening

The default upstream kernel configuration prioritizes compatibility over security. For a hardened environment, specific sysctl parameters must be tuned to restrict memory access and network stack behavior.

Below is a production-grade /etc/sysctl.d/99-security.conf snippet targeting memory protection and network hardening.

# --- Kernel Self-Protection ---

# Restrict access to kernel pointers in /proc/kallsyms

# 0=disabled, 1=hide from unprivileged, 2=hide from all

kernel.kptr_restrict = 2

# Restrict access to the kernel log buffer (dmesg)

# Prevents attackers from reading kernel addresses from logs

kernel.dmesg_restrict = 1

# Restrict use of the eBPF subsystem to privileged users (CAP_BPF/CAP_SYS_ADMIN)

# Essential for preventing unprivileged eBPF exploits

kernel.unprivileged_bpf_disabled = 1

# Turn on BPF JIT hardening (blinding constants)

net.core.bpf_jit_harden = 2

# --- Network Stack Hardening ---

# Enable IP spoofing protection (Reverse Path Filtering)

net.ipv4.conf.all.rp_filter = 1

net.ipv4.conf.default.rp_filter = 1

# Disable ICMP Redirect Acceptance (prevents Man-in-the-Middle routing attacks)

net.ipv4.conf.all.accept_redirects = 0

net.ipv4.conf.default.accept_redirects = 0

net.ipv6.conf.all.accept_redirects = 0

Apply these changes dynamically with sysctl -p /etc/sysctl.d/99-security.conf. Refer to the official kernel sysctl documentation for granular details on specific parameters.

3. Syscall Filtering with Seccomp BPF

Secure Computing Mode (Seccomp) is critical for reducing the kernel’s exposure to userspace. By default, a process can make any system call. Seccomp acts as a firewall for syscalls.

In modern container orchestrators like Kubernetes, Seccomp profiles are defined in JSON. However, understanding how to profile an application is key.

Profiling Applications

You can use tools like strace to identify exactly which syscalls an application needs, then blacklist everything else.

# Trace the application and count syscalls

strace -c -f ./my-applicationA basic whitelist profile (JSON) for a container runtime might look like this:

{

"defaultAction": "SCMP_ACT_ERRNO",

"architectures": [

"SCMP_ARCH_X86_64"

],

"syscalls": [

{

"names": [

"read", "write", "exit", "exit_group", "futex", "mmap", "nanosleep"

],

"action": "SCMP_ACT_ALLOW"

}

]

}Advanced Concept: Seccomp allows filtering based on syscall arguments, not just the syscall ID. This allows for extremely granular control, such as allowing `socket` calls but only for specific families (e.g., AF_UNIX).

4. Kernel Module Signing and Lockdown

Rootkits often persist by loading malicious kernel modules. To prevent this, enforce Module Signing. This ensures the kernel only loads modules signed by a trusted key (usually the distribution vendor or your own secure boot key).

Enforcing Lockdown Mode

The Linux Kernel Lockdown feature (available in 5.4+) draws a line between the root user and the kernel itself. Even if an attacker gains root, Lockdown prevents them from modifying kernel memory or injecting code.

Enable it via boot parameters or securityfs:

# Check current status

cat /sys/kernel/security/lockdown

# Enable integrity mode (prevents modifying running kernel)

# Usually set via GRUB: lockdown=integrity or lockdown=confidentiality5. Runtime Observability & Security with eBPF

Traditional security tools rely on parsing logs or checking file integrity. Modern Linux Kernel Security leverages eBPF (Extended Berkeley Packet Filter) to observe kernel events in real-time with minimal overhead.

Tools like Tetragon or Falco attach eBPF probes to syscalls (e.g., `execve`, `connect`, `open`) to detect anomalous behavior.

Example: Detecting Shell Execution in Containers

Instead of scanning for signatures, eBPF can trigger an alert the moment a sensitive binary is executed inside a specific namespace.

# A conceptual Falco rule for detecting shell access

- rule: Terminal Shell in Container

desc: A shell was used as the entrypoint for the container executable

condition: >

spawned_process and container

and shell_procs

output: >

Shell executed in container (user=%user.name container_id=%container.id image=%container.image.repository)

priority: WARNINGFrequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Does enabling Seccomp cause performance degradation?

Generally, the overhead is negligible for most workloads. The BPF filters used by Seccomp are JIT-compiled and extremely fast. However, for syscall-heavy applications (like high-frequency trading platforms), benchmarking is recommended.

What is the difference between Kernel Lockdown “Integrity” and “Confidentiality”?

Integrity prevents userland from modifying the running kernel (e.g., writing to `/dev/mem` or loading unsigned modules). Confidentiality goes a step further by preventing userland from reading sensitive kernel information that could reveal cryptographic keys or layout randomization.

How do I handle kernel vulnerabilities (CVEs) without rebooting?

For mission-critical systems where downtime is unacceptable, use Kernel Live Patching technologies like kpatch (Red Hat) or Livepatch (Canonical). These tools inject functional replacements for vulnerable code paths into the running kernel memory.

Conclusion

Mastering Linux Kernel Security is not a checklist item; it is a continuous process of reducing trust and increasing observability. By implementing a layered defense—starting with strict LSM policies, minimizing the attack surface via sysctl, enforcing Seccomp filters, and utilizing modern eBPF observability—you transform the kernel from a passive target into an active guardian of your infrastructure.

Start by auditing your current sysctl configurations and moving your container workloads to a default-deny Seccomp profile. The security of the entire stack rests on the integrity of the kernel. Thank you for reading the DevopsRoles page!